Monday, January 30, 2017

The Choice of King Midas, 1873 Poem

THE CHOICE OF KING MIDAS, from the American Journal of Numismatics 1873

“GOLD, gold, money untold!"

Cried Midas to Bacchus, beseeching.

Said the god, “I’m afraid,

By the prayer you have made,

You are vastly too overreaching.

But the gold I will grant,

Aye, more than you want."

Said Midas, “My coffer

Holds more than your offer,

So grant me the treasure without stint or measure."

Gold, gold, money untold,

King Midas found came to his wishes:

Wherever he trod,

Rich gold was his sod;

Gold covered his meat and his dishes!

No mint more prolific,

His touch was specific,

And turned all to ore that was gold to the core.

Gold, gold, money untold! “Alas!" cried the monarch, confounded,

"I would rather, I think,

Have good victuals and drink

Than be with such metal surrounded.

Mighty Bacchus, I pray,

Let your gift pass away,

For gold of itself can no hunger allay!"

“Gold, gold, money untold,” Said the god to the penitent miser,

“Is a gift of no worth

To the children of earth,

Nor makes them the better or wiser!

But a way I'll unfold

To wash off your gold,

If you wish me to be your adviser."

“Gold, gold, money untold,

To be rid of you I will endeavor."

So the King laid aside

Both his robes and his pride,

And plunged into Pactolus River.

From his skin fell away

All the gold, strange to say,

And is left in the sands there forever!

Though good is gold, to have and hold,

This story makes it clear,

Who sells himself for sordid pelf,

Has bought it much too dear!

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

MIDAS by Jones Very 1886

Turn all I touch to gold,

King Midas said.

His wish was granted, and behold!

His very meat was gold, and gold his bread.

And liquid gold the drink

He raised on high,

When o'er the golden goblet's brink

The water to his eager lips came nigh.

Ah, fatal gift! that balked

His greedy soul;

Which in its very richness mocked;

For gold is but one thing, and not the whole.

So they, who money seek,

Gold, only gold,

Are childish, disappointed, weak,

Though gained their end; like that famed king of old.

Tuesday, January 24, 2017

Climate Change fears in the Nineteenth Century

From "Memoirs and Reminiscences" written by the Reverend Casper Schaeffer, M.D. in 1855

Download this book for a limited time here.

For a list of all of my digital books and disks click here

(Pages 67 and 68):

"Formerly the snows fell much deeper and the winters were more severe in this country than in late years. I have heard my father say that in the winter of 1780-81 that the depth of snow was such that in traveling they did not confine themselves to the road, but drove over fences and across fields, the snow being sufficiently hard to bear them, since which period the weather at that season has been gradually growing milder; so much so that some winters will pass with scarcely snow enough for any sleighing. Is is now a very rare thing for the Delaware to be frozen over, whereas formerly this was an ordinary occurrence. Evidently our climate is ameliorating and becoming similar in temperature to the same degree of latitude on the European continent. Now as to the cause of this change various opinions are entertained, some assigning one cause and some another. My own long-cherished opinion is that it is owing principally to two things: first, to the clearing away the forests and opening up the swamps, whereby the surface of the ground being exposed to the action of the sun and the accumulated moisture being evaporated, the ground becomes dryer and consequently warmer. A second cause contributing, I think, in no small degree to the same effect, is the cultivation of the soil; the action of the plow, in turning up the sub-soil, thus loosening the ground and exposing a greater surface to the action of the sun, consequently also producing increased dryness and warmth. With the increased heat of the ground, the temperature of the atmosphere is likewise increased, consequently less snow falls and is sooner melted. These several causes continuing to act, the probability is that in the course of time, our climate will assimilate to the mildness of the same latitudes in western Europe. The gulf stream, however, exercises a benign influence upon that country which is experienced in a much less degree in our own country."

From Nature magazine 1883:

A recent correspondent of Nature is very much worried about the earth's atmosphere, which, he says, has become so polluted by the hurning of coal that in the year 1900 all animal life upon the globe will cease, killed by carbonic dioxide. Another correspondent joining this prophet of evil, shows that while most of the gas is washed out of the air by rain, some products of combustion (or rather incomplete combustion), as hydrogen and the hydrocarbons remain. Of these unburned gases 100,000,000 tons have escaped into the air within thirty years. What will be the result of this

accumulation? According to Professor Tyndall hydrogen, marsh gas and ethylene have the property in a very high degree of absorbing and radiating heat. From this we may conclude, says the correspondent, that the increasing pollution of the atmosphere will have a marked influence on the climate of the world. The mountainous regions will be colder, the Arctic regions will be colder, the tropics will be warmer and throughout the world the night will be colder and the days warmer. In the temperate zone winter will be colder and winds, storms and rain-fall greater.

Pollution of the Atmosphere, from Nature Dec. 7, 1882

But there are other products of combustion, or rather of incomplete combustion, that are not brought down in this manner by rain, as hydrogen and the hydrocarbons, chiefly marsh-gas and ethylene. The latter has, I believe, been observed by the spectroscope on the Alps, and was supposed to have come from space.

Since the year 1854 (as near as I can estimate) there has been burnt 10,000 million tons of coal; and if we say (in its consumption by household grates, leakage by gas-pipes, &c.) 1/100th escapes, then 100 million tons of hydrogen and hydrocarbons are floating in the atmosphere, or 1/10,000,000th part in bulk; if we say the average proportion of hydrogen to be '45, and of marsh gas '35, and of ethylene '4, we have '84 per cent, of gases that are lighter than air, and it is more than probable that the law of diffusion of gases, as demonstrated with jars, does not apply to the atmosphere. The cases are not parallel: in the air we have unconfined space, pressure, and temperature diminishing infinitely, conditions favourable to the lighter and the gas with the greater amount of specific heat rising and maintaining its elevation, especially as we know that in large halls carbonic dioxide is found in larger quantities on the floor. According to Prof. Tyndall's researches, hydrogen, marsh gas, and ethylene have the property in a very high degree of absorbing and radiating heat, and so much so that a very small proportion, of only say one thousandth part, had very great effect. From this we may conclude that the increasing pollution of the atmosphere will have a marked influence on the climate of the world. The mountainous regions will be colder, the Arctic regions will be colder, the tropics will be warmer, and throughout the world the nights will be colder, and the days warmer. In the Temperate Zone winter will be colder, and generally differences will be greater, winds, storms, rainfall greater. H. A. Phillips Tanton House, Stokesley, November 23

From The New Century, January 11, 1903

Future Glacial Periods

THE New York American and Journal has been Collecting the opinions of a number of scientific authorities as to whether another Ice Age is due. Geological records show such ages to have been periodical and recurrent in the past, and astronomers have endeavored to link them with changes in the earth's bearings.

This agrees with the teachings of Madame Blavatsky and William Q. Judge, and the former discusses and quotes many scientific utterances, showing where they are wrong and indicating the true explanation and the true figures.

From the Journal article we gather that Prof. W. O. Crosby thinks our climate is becoming refrigerated, because so many fossil mollusks and shells have been dug up in Boston harbor and the Charles river, which represent forms that now live only in more southern waters. He also says that Greenland a thousand years ago had flourishing colonies of Norsemen all along its shores, while now the Eskimos are the only inhabitants; and that Iceland was much milder when settled upon by the Norsemen in 874.

The United States Geological Survey is studying the question, and the International Congress of Geologists has appointed a committee to investigate it.

Prof. W. L. Elkin is reported as saying that the changes in the inclination of the earth's axis make long astronomical summers and winters of 10,500 years each; and that about 600 years ago we entered on one of the winters (in the northern hemisphere).

There is much evidence to show that Northern climates have been growing colder since the last Ice Age. Part of New England was called by the early Scandinavian explorers "Vinland," on account of the vines there. There is much to indicate that the American continent has grown colder since its occupation by Europeans. Dr. Edward Everett Hale points out that foreign grapes and subtropical plants ripened around Boston 100 years ago. In Northern Europe and Asia historical testimony points the same way. H. P. Blavatsky says on this subject:

"Glacial Periods" were numerous, and so were the "Deluges," for various reasons. Stockwell and Croll enumerate some half-dozen Glacial Periods and subsequent Deluges — the earliest of all being dated by them 850,000 years ago.

All this goes to show that the semi-universal deluge known to Geology — the first Glacial Period — must have occurred just at the time allotted to it by the Secret Doctrine: namely, 200,000 years, in round numbers, after the commencement of our Fifth Race, or about the time assigned by Messrs. Croll and Stockwell for the first Glacial Period: i.e., about 850,000 years ago. All such cataclysms are periodical and cyclical.

Friday, January 20, 2017

Socialism the Creed of Despair by George Hugo 1909

Socialism the Creed of Despair by George B. Hugo 1909

See also The History & Mystery of Money & Economics-250 Books on DVDrom and 500 Books on 2 DVDROMs for Libertarians and Objectivists

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks, click here

I am an individualist. I acknowledge no master on earth except the law! I am an individualist who favors the utmost social and economic freedom consistent with the freedom of every other individual. In other words, my freedom, my liberty, my rights, cease the moment I encroach upon the freedom, liberty, or rights of another individual. This is the fundamental theory of freedom, religious, political, and economic,—-the true conception of freedom and ideal individualism. In defence of this ideal I shall attempt to puncture the tires of the menacing red devil of Socialism before individualism is crushed to death.

Socialism from beginning to end can be summed up in one sentence: Socialism is the puny attempt of visionary mortals to change nature's unalterable law. Socialism is an emotional debauch, the morphine stimulant of a decaying civilization, the opium exhilaration, intoxication, coma, and death of a nation adopting it.

The economic struggle confronting us is not between Capital and Labor, but between individualism and collectivism, between the man who has and the man who has not, between intelligence and ignorance, between mental power and hand power. It is the struggle for supremacy, between the mental giant representing intelligence and capacity-—the ideal in civilization, all that is noble and worth while, the soul of life-—and the physical giant representing ignorance, incapacity, and brute force, seeking only the happiness of the beast, a satiated belly, soulless materialism. Properly defined, individualism means progressive civilization, order, and liberty. Collectivism means retrogression, chaos, compulsion, and, at its best, state servitude. As religion and humanity constitute the soul of true civilization, so individual ownership of property is the material foundation of civilization. When collectivism, or Socialism, with its unbalanced intellectuals, its mushy sentimentalists, its vicious, its discontented, its failures in life, attacks the private property of the individual, it becomes a menace to modern civilization and cannot be tolerated.

What is property, or capital, and how is it created? Capital is the result of labor performed by an individual in excess of his living requirements. To illustrate: If eight hours a day is necessary to provide food, clothing, and shelter for an individual, or for an individual and those depending upon him, and the individual worked but eight hours a day, there would be no surplus or capital remaining. Should he, however, work for ten or more hours, whatever remained over and above his requirements of that day would be so much surplus wealth or capital. Thus we find that all capital is primarily created by excess labor. There must be no misunderstanding about the term "labor." It is probably safe to say that 90 per cent, of those who accept the theory of Socialism understand "labor" to mean only physical results, the work of the body. They place no value on intellectual labor, which is the great source of wealth to them. In other words, they must be able to see, feel, hear, taste, or smell results, or they have no value. This is the common conception of the term "labor" by the mass of physical workers, and is generally accepted by the unthinking.

Thought, the greatest force in the world for the uplift of mankind, not being a tangible substance, is considered of no value in the socialistic scheme. Creative power, ability, and directing capacity, the result of thought and absolutely essential for progress in the industrial field, the brains and head of the body politic, are to be chopped off, and the tangled mass of legs, arms, and trunks are to automatically perform the world's work. By some unknown mystical process, nature's laws will be changed. Greed, avarice, and all human ills are to disappear. Frail humanity will shake off its defects, mankind will become God-like, and perfect equality will be the order of the universe. What a beautiful picture! But what a pipe-dream! Emotionalists look upon this picture with frenzied enthusiasm, suffering humanity grasps at this straw of quackery for relief, while sane men look on with compassionate sympathy and dread of the inevitable consequences. The cumulative experience and wisdom of the ages are to be superseded by a fantastic scheme of topsy-turvy-dom called Socialism,—-certainly a cheerful outlook for the individual!

The cry of mediocrity,-—"Labor creates all. Labor is entitled to all it produces. Labor is entitled to all the land. Labor is entitled to hold all the machinery,"—-these are the stock claims made by Socialists. Give labor land, machinery, and all the raw material in the world, including factories and plants of every description, without a master mind to direct its operation, it would be as helpless as a child in swaddling-clothes, as dangerous as a train of cars and engine on the track with steam up, the throttle in the hands of incompetence. God only could save that train from wreckage! It must be conceded, then, that intelligent direction is of more importance to industry than physical labor.

With the facts fundamentally established that capital is the result of excess labor, both physical and intellectual, and further established that both are necessary to create capital, the question of distribution arises. How shall it be distributed? The method of distribution raises two questions:—

(1) Shall the capital produced by labor—-both physical and intellectual—-be distributed in proportion to the amount each individual creates?

Should Socialism answer No, then what becomes of its claim that labor is entitled to all it produces? If, however, it answers Yes, there can be no disagreement about existing conditions. Now for the second question:—

(2) Shall the capital produced by both classes be cast into a common pool for equal distribution among all workers, regardless of the amount each individual has created?

This question is the meat in the coconut, the rock upon which Socialist and individualist split. Should Socialism answer Yes, its demand for equality of opportunity is untenable by the fact that common justice demands that the equal right or opportunity to take from the common pool carries with it the obligation of an equal contribution to the common pool. If, on the other hand, the obligation of equal contribution is to be ignored, then individuals contributing the larger shares of capital to the pool will be at a decided disadvantage in the socialistic scheme of equality and equal opportunity. J. Phelps Stokes, acknowledged authority on Socialism, is quoted as saying, "We don't ask people to join the Socialist Party, unless they understand Socialism is just and fair." I should like to ask if the individuals contributing the larger share of capital to the common pool would be treated "just and fair" under this arrangement?

"But," say the more advanced of the fifty-seven varieties of Socialism, "we concede that intelligent direction is essential, but the difficulty is that these directors receive an unjust proportion of the capital produced. In other words, hand labor does not receive a just proportion of what it produces, which recalls to my mind the story of the walking delegate of the Hack Drivers' Union during a strike in San Francisco. In conversation with the prosecuting attorney, after the conviction of a peaceful (?) picket caught in the act of using one of those peaceful instruments of persuasion, commonly called a "black-jack", he said to the district attorney, "You know very well that labor does not get a just proportion of what it produces." The attorney replied, "Oh, I don't know about that." "You know they don't." "Now let us see," replied the attorney. "You are a hack driver. What do you produce?" The hack driver scratched his head a moment, and then replied: "What do I produce? Motion."

But let us analyze the statement that hand labor does not get a just proportion of what it produces by a concrete illustration. Supposing that a hundred hatters (very apropos just now), working independently, can each make one hat a day, paying $2 for material and selling at $4, leaving $2 for their pay. Then an individual comes along, invents machinery, puts up a factory, and induces the hundred hatters to go into the factory and work according to his direction. The hundred hatters turn out two hundred hats a day instead of one hundred, with a value of $800 instead of $400, in less time and under better conditions than when working separately. Who created and who is entitled to the difference in value? The hundred hatters or the individual who by his inventive genius and directing ability created the difference in value? But let us go a step farther, and assume that he paid the hatters twenty-five cents a day more than they could make separately, and reduced the price of hats to consumers twentyfive cents also. Could either the hatters or the purchasers of hats claim that they had been injured by the change? Will not even the most rabid Socialist concede that the individual is entitled to the extra value he created? But, as this illustration involves machinery and a factory, some question might be raised in the Socialist mind about ownership of the machinery.

I will get a little closer to earth by giving another illustration. Supposing two men own apple orchards side by side. One by care and scientific application of the art of raising apples produces a better grade of apple than his neighbor's, so that he receives five dollars a barrel for his apples, the other receiving only three dollars for apples of an inferior grade. The difference is a difference of product, one superior to the other. Is the individual who raises the better apples entitled to the difference in value? Should he pay his farm hands more for doing the same work that his neighbor's men are doing? in other words, divide the fruit of his own genius with the men who chanced to be working for him instead of for his neighbor? Did he not produce the difference in value, and is he not entitled to all he produces according to the Socialist theory, that labor is entitled to all it produces? Could any one claim that the greater share in this transaction is not a just proportion to which the individual is entitled? I think not.

John Spargo says, "When you say 'Equality of Opportunity,' you express the whole aim of modern Socialism." I would like to ask if both these men who owned the orchards side by side did not have an equal opportunity to raise the same quality of apples? The opportunity was the same; but was it not the difference between intelligence and ignorance, ambition and laziness, will to do and unwillingness to do? Nature's inequality of the human being. Does any one believe that nature's law would be changed by the adoption of the socialistic scheme of government? Does this not prove that Socialism is but a visionary ideal, without a practical working basis? As a purely economic proposition or, as some put it, "a bread-and-butter proposition," its realization of equality is a practical impossibility.

I shall now quote from the Socialist Party Platform handed to me by my Socialist brother, Mr. Carey, as his particular brand of Socialism, so that I should not discuss one of the other fifty-six kinds only to find that my arguments did not apply to the right one:—

"Human life depends upon food, clothing, and shelter. Only with these assured are freedom, culture, and higher human development possible. To produce food, clothing, and shelter, land and machinery are needed. Land alone does not satisfy human needs. Human labor creates machinery, and applies it to the land for the production of raw materials and food. Whoever has control of land and machinery controls human labor, and with it human life and liberty."

Then in the last paragraph we find:—

"To unite all workers of the nation and their allies, and sympathizers of all other classes to this end, is the mission of the Socialist Party. In this battle for freedom the Socialist Party does not strive to substitute working-class rule for capitalist-class rule, but by working-class victory to free all humanity from class rule, and to realize the International Brotherhood of Man."

Now that sounds well, especially the words "battle for freedom," "to free all humanity from class rule," "the Brotherhood of Man."

We as individualists accept this plank, and, paradoxical as it may seem to you, I am on this platform to-night to uphold this sacred principle of freedom. So long as there is a spark of life within me, I shall be on the firing line of the battle for freedom, the battle to free all humanity from class rule, and to practise the Brotherhood of Man.

But how does Socialism live up to this plank? By catering to organized labor, the tail to its kite. With few exceptions every Socialist is a unionist, and every unionist is a Socialist, though he does not always know it. I never could quite reconcile the two, but Socialism indorses organized labor, accepts its label, that odious mark of servility, coercion, and tyranny printed on the very tickets which brought you in here to-night. And, thus indorsing organized labor, Socialism stands sponsor for its inhuman acts. Organized labor, one of whose spokesmen, the notorious Shea, stood upon this platform and said, "The time has come when a man must be a member of a labor organization or be in the hospital." He went to Chicago, and made a record of killing eighteen men and injuring four hundred and fifty others. I want to ask you, Is this freedom? Is this the Brotherhood of Man? Organized labor, which denies boy or man the opportunity to learn a trade. Is this freedom? Is this the doctrine of the Brotherhood of Man? Organized labor that kills, slugs, and terrorizes individuals who do not do its bidding? Is this freedom? Is this the practice of the Brotherhood of Man?

How do you as Socialists reconcile yourselves to these inhuman acts? Is the battle for freedom to be won through organized labor troops of compulsion, led by the Socialist generals of discontent, who mistake slavery for freedom? Is humanity to be freed from class rule by the rule of despotic mediocrity? Is humanity to sell itself into slavery for food, clothing, and shelter? This the black slave always had. This is the brotherhood of the beast,—-the cow, horse, and dog,—-not the Brotherhood of Man. Civilized men will never sell their freedom to any collective group, be they capitalists, unionists, or Socialists, for food, clothing, and shelter. Individual freedom means more than a satiated belly. It will not give up its individualized entity, and become an automatic instrument under the domination and control of any collective group. Socialism is a menace to modern civilization. Why?

(1) Because it is a step backward,—-retrogression.

(2) It would destroy man's power of individual choice.

(3) It would relieve man from the personal responsibility and moral obligation which he owes his fellow-man.

(4) It would reduce man to the status of an automaton.

(5) It would destroy Free Will, the foundation of moral accountability to God.

(6) Because it is an economic fallacy and a spiritual delusion.

There may be those who are willing to shift upon the State the responsibility they owe to themselves and their fellow-men. But let me say there can be no escape. The debt we owe to life is a debt that each individual must pay himself.

For a list of all of my digital books and disks click here

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

The History and Mystery of Money & Economics-250 Books on DVDrom

Only $5.99 (I only ship to the United States)

Only $5.99 (I only ship to the United States)

Books Scanned from the Originals into PDF format

Contact theoldcdbookshop@gmail.com for questions

Books are in the public domain. I will take checks or money orders as well.

Contents of disk:

The Wealth of Nations, Volume 1 by Adam Smith 1910

The Wealth of Nations, Volume 2 by Adam Smith 1910

The Wealth of Nations, Abridged, 1884 (Students Edition)

The Rothschilds - the Financial rulers of nations by John Reeves 1887

A Treatise on Political Economy by Jean Baptiste Say 1830

The Dismal Science, a Criticism on Modern English Political Economy by William Dillon 1882

Social Value - a study in economic theory, critical and constructive by Benjamin Anderson 1911

The Value of Money by Benjamin Anderson 1917

Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Volume 1 by Charles Mackay 1850

Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Volume 2 by Charles Mackay 1850

Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Volume 3 by Charles Mackay 1850 (a classic work that discusses the Tulip Bubble in the 17th century)

Man, Money, and the Bible - Biblical Economics by John R Allen 1891

Unto this Last & other Essays on art and Political Economy by John Ruskin 1907

Principles of political economy by Thomas Malthus 1821

An Essay on the Principle of Population, Volume 1 by Thomas Malthus 1817

An Essay on the Principle of Population, Volume 2 by Thomas Malthus 1817

An Essay on the Principle of Population, Volume 3 by Thomas Malthus 1817

The Coins of the Bible and its Monetary Terms by James R Snowden 1864

The Money of the Bible by George C Williamson 1894

Capital and Interest, a critical history of economical theory by Eugen Von Bahm-Bawerk 1890

Karl Marx and the Close of His System by Eugen Von Bahm-Bawerk 1898

Lombard Street, a description of the Money Market by Walter Bagehot 1920

The Principles of Economics with applications to practical problems by Frank A Fetter 1904

Source book in Economics by Frank A Fetter 1913

Principles of economics, Volume 1 by Alfred Marshall

Elements of Economics of Industry 1 by Alfred Marshall

Industry and Trade by Alfred Marshall 1920

Capital by Karl Marx 1904

Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx 1906

Political Economy, by Simonde de Sismondi, 1847

An Inquiry into the Principles of political Economy by Sir James Steuart, Volume 1, 1767

An Inquiry into the Principles of political Economy by Sir James Steuart, Volume 2, 1767

A Select Collection of Scarce and Valuable Economical Tracts (Defoe, Elking, Franklin, Turgot, Anderson, Schomberg, Townsend, Burke, Bell) 1859

Principles of Political Economy with some of their applications to social philosophy by John Stuart Mill 1920

An Introduction to the Theory of Value on the lines of Menger, Wieser, and Bohm-Bawerk by William Smart 1891

Belgian Democracy by Henri Pirenne 1915

The Works of David Ricardo 1888

The principles of political economy & taxation by David Ricardo 1912

Essays on some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy by John Stuart Mill 1874

On the Concept of Social Value by Joseph Schumpeter 1909

Socialism and the social movement by Werner Sombart 1909

Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy 1917 (the classic fictional story of Julian West, a young American who, towards the end of the 19th century, falls into a deep, hypnosis-induced sleep and wakes up 113 years later. He finds himself in the same location but in a totally changed [Socialistic] world)

The People's Marx (Abridged version of Capital) 1921

The Marxian Economic Handbook and Glossary by WH Emmett 1922

The Political Theories of P.J. Proudhon by Shi Yung Lu 1922

What is Property, By Pierre Joseph Proudhon 1840

The State - Its Nature, Object, and Destiny By Pierre Joseph Proudhon 1849

The Vatican - its History, its Treasures by Ernesto Begni 1914

The Tithe in Scripture by Henry Landsdell 1908

Mediaeval Socialism by Jarrett Bede 1914

An Introductory Lecture on Political Economy by Nassau William Senior 1827

Three lectures on the rate of wages by Nassau William Senior 1830

The engineers and the price system by Thorstein Veblen 1921

The Theory of the Leisure Class, an economic study of institutions by Thorstein Veblen 1918

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by Max Weber 1920

The Physiocrats, 6 lectures on the French économistes of the 18th century by Henry Higgs 1897

The Gentle Art of Train Robbery by Jack Comegys 1905

Professional Criminals of America by Thomas Byrnes 1886

Economic History of the United States by Ernest L Bogart 1914

Economic History of England by M Briggs 1914

The Theory and History of Banking by Charles Dunbar 1922

Train and Bank Robbers of the Wild West 1889

True History of the so-called £1,000,000 Forgery, the bank duped: how the impregnable Bank of England showered its bags of gold on George Bidwell

The Economic Interpretation of History by Edwin Seligman 1902

Guild Socialism by Niles Carpenter 1922

The Case for Capitalism by Hartley Whithers 1920

Both Sides of the Tariff Question by the world's leading men 1890

Protectionism, the -ism which teaches that waste makes wealth by William Graham Sumner 1885

History of Economic Thought by Lewis Haney 1922

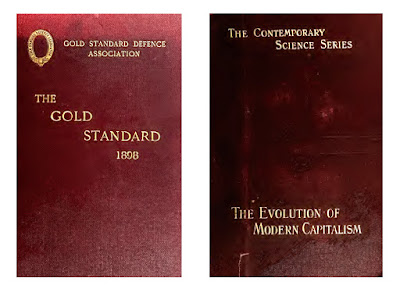

The Evolution of Modern Capitalism by JA Hobson 1907

The Roosevelt Panic of 1907 By Adolph Edwards 1907

The Causes of the Panic of 1893 by W. Jett Lauck 1907

A Short History of Coins and Currency by Sir John Lubbock 1902

United States Notes - a History of the various issues of paper money by the Government of the United States by John Jay Knox 1899

The Gold Standard by Gold standard defence association 1898

The Gold Standard: its causes, its effects, and its future by Wilhelm von Kardorff-Wabnitz 1880

New View Of Society by Robert Owen 1813

Letters to Malthus on Political Economy by Jean Baptiste Say 1821

Elements of Political Economy by James Mill 1826

Overproduction and Crises by Johann Karl Rodbertus 1908

General Theory of Political Economy by William Stanley Jevons 1886

Imperialism - A Study by John A Hobson 1902

Dictionary of Political Economy, Volume 1 by Sir Robert Palgrave 1915

Dictionary of Political Economy, Volume 2 by Sir Robert Palgrave 1915

Dictionary of Political Economy, Volume 3 by Sir Robert Palgrave 1915

Economic interpretation of history by James E Rogers 1888

Economic Determinism by Lida Parce 1913

The philosophy of wealth by John Bates Clark 1894

Principles of the economic philosophy of society, government and industry by Van Buren Denslow 1888

History of economics by Joseph Dewe 1908

Jesus an Economic Mediator bA treatise on political economy; (1830)y James Darby 1922

On the Principles of Political Economy by David Ricardo 1821

Outline of Economic by Richard Ely 1918

Political Economy For Beginners by MG Fawcett 1911

The Austrian Economists and their View of Value, article in the Journal of Economics 1889

Popular fallacies regarding trade by Frederic Bastiat 1882

Fallacies of protection by Frederic Bastiat 1909

Popular Fallacies Regarding General Interests by Frederic Bastiat 1849

An Introduction to the Study of Political Economy by Luigi Cossa 1893

The cause of business depressions as disclosed by an analysis of the basic principles of economics by Hugo Bilgram 1914

The federal reserve system by Henry Parker Willis 1920

The Federal reserve monster by Sam Clark 1922

The economics of socialism by HM Hyndman 1921

The economics of Herbert Spencer by Owen William 1891

LIBERTY AND TAXATION by Benjamin Tucker

Calumet K

This 1901 book is the story of one man's ingenuity, perseverance and struggle in the construction of a grain elevator and of his exhilarating triumph.

Ayn Rand considered this her favorite novel, and wrote that "it has one element that I have never found in any other novel: the portrait of an efficacious man."

Political Economy For Beginners by MG Fawcett 1900

The Austrian Economists, article in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 1890

Facts and figures, the basis of economic science by E Atkinson 1904

The Case against Protection by E Cooke 1909

Fair trade unmasked by the Cobden Club 1887

Principles of Scientific Management by Frederick Winslow Taylor 1911

Inflation by J Shield Nicholson 1919 (The Abandonment of the Gold Standard During the War)

How the Federal Reserve was Evolved by 5 Men in Jekyl Island, article in the Current Opinion 1916

An Economic History of Rome by Tenney Frank 1920

Currency inflation and public debts by Edwin Seligman 1921

Fiat Money Inflation in France, how it came, what it brought and how it ended by Andrew Dickson White 1914

A Brief History of Pawnbroking by Alfred Hardaker 1892

Sound Money Monographs by William C Cornwell 1897 (Should Government Retire from Banking?, Gold Standard etc)

The History of Money in America by Alexander Del Mar 1899

The Science of Money by Alexander Del Mar 1899

Lorenzo de Medici and Florence in the 15th century by Edward Armstrong 1908

The Elements of the Science of Money by John Prince Smith 1813

Historical Summary of Metallic Money by Robert N Toppan 1884

The Mississippi Bubble: a Memoir of John Law by Adolphe Tiers 1859

John Law of Lauriston, Financier and Statesman, founder of the Bank of France, originator of the Mississippi Scheme by AW Wiston-Glynn 1907

The Financial Philosophy - The Principles of the science of money by George Wilson 1895

The Economic Principles of Confucius by Chen Huan-Chang 1911

The Law of Oresme, Copernicus, and Gresham by Thomas W Balch 1908

The Life Story of J. Pierpont Morgan by Carl Hovey 1911

Bulls and Bears of New York: With the Crisis of 1873 by Matthew Hale Smith - 1874

Economic Essays by Charles F Dunbar 1904 (Economic science in America, 1776-1876, The reaction in political economy, Ricardo's use of facts, Some precedents followed by Alexander Hamilton, The direct tax of 1861, The new income tax, Early banking Schemes in England, The bank of Venice etc)

My Adventures with Your Money by George Graham Rice 1913 (Dedicated to: To The American Damphool Speculator, surnamed the American Sucker, otherwise described herein as The Thinker - Who Thinks He Knowsi But Doesn't - Greetings. This book is for you! Read as you run, and may you run as you read.)

A History of Banking in all the Leading Nations, Volume 1 by William Graham Sumner 1896

A History of Banking in all the Leading Nations, Volume 2 by William Graham Sumner 1896

A History of Banking in all the Leading Nations, Volume 3 by William Graham Sumner 1896

A History of Banking in all the Leading Nations, Volume 4 by William Graham Sumner 1896

Coins & Medals as Aids to the Study and Verification of Holy Writ by Stanley Clark Bagg 1863

Mohammedan (Islamic) Theories of Finance by Nicolas P Aghnides 1916

Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie 1920

The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie 1901

The Rise and Progress of the Standard Oil Company by Gilbert H Montague 1903

Life of P. T. Barnum, Written by himself, Including his golden rules for Money-making 1888

The Story of Money - A Science Hand-book of Money Questions by E.C. Towne 1900

Gold and Silver as Currency - in the light of experience, historical, economical, and practical by James G Patterson 1896

Bimetallism - a summary and examination of the arguments for and against a bimetallic (Gold and Silver) system of currency by Leonard Darwin 1898

Monetary Economics by William W Carlile 1912

Economic method and economic fallacies by William W Carlile 1904

Monetary and industrial fallacies by John B Howe 1878

Abraham Lincoln - Protectionist 1916

Financial History of the United States by Davis R Dewey 1920

The Gilded Age by Mark Twain 1873

Acres of Diamonds by Russell Conwell 1915

My Life and Work by Henry Ford 1922

Way to Wealth by Benjamin Franklin 1814

The Art of Worldly Wisdom by Baltasar Gracián y Morales 1904

Pushing to the Front - Success under difficulties by Orison S Marden 1911

Paper against Gold - the Mystery of the Bank of England of the debt of the stocks of the sinking fund and of all the other tricks and contrivances carried on by the means of paper money by William Cobbett 1846

Legal Tender, a study in English and American Monetary History by Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge, 1903

Great Britain in the latest Age, from laisser faire to State Control by AS Turberville 1921

The Story of Modern Progress by Willis M West 1920

The Struggle for Bread by Victor W Germains 1913

The Corner in Gold - Its History and Theory by FW Bain 1893

History of the Terrible Financial Panic of 1873

The History of Currency, 1252 to 1894 by William Arthur Shaw 1895

A History of Commerce by Clive Day 1916

A History of the Precious Metals by Alexander Del Mar 1902

History of Monetary Systems, record of actual experiments in money made by various states of the ancient and modern world by Alexander Del Mar 1895

Paper Money, the money of civilization by James Harvey 1877

Money and Civilization by Alexander Del Mar 1886

The Mystery of Money Explained By James Taylor 1862

Tendencies in American Economic Thought By Sidney Sherwood 1897

The Economics of Laissez Faire by Harris Gilbert Franklin 1920

A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy by Karl Marx 1904

Economic Liberalism by Hermanm Levy 1913 (keep in mind that 100 years ago "Liberalism" had a more libertarian [Laissez Faire] definition)

The Industrial Revolution by Charles Beard 1919

Marxian (Karl Marx) Economics by Karl Untermann 1911

The Remarkable History of the Hudson's Bay Company by George Bryce - 1900

Paper Money, the Root of Evil by Charles A. Mann - 1872

Benjamin Franklin as an Economist by WA Wetzel 1895

Contributions of Alchemy to Numismatics by Henry Carrington Bolton 1890

Economics for the People - Plain Talks on Economics by RR Bowker 1892

Economics for Beginners by Henry Dunning Macleod 1879

Political Economy for Beginners by Millicent Garrett Fawcett 1911

Antiquity of Coins by William Hume 1856

The President and the Motto on our Coins 1908 (In God We Trust)

Psychology of the Stock Market by GC Selden 1912

The Pitfalls of Speculation by Thomas Gibson 1916

Wall Street Speculation, its Tricks and its Tragedies by Francis C Keyes 1904

Betting and gambling by Seton Churchill 1894

Gambling (Fortuna) -The True Philosophy and Ethics of Gambling by James H Romain 1891

The New Philosophy of Money by Alfred B Westrup 1895

The Financial Philosophy - The Principles of the Science of Money by George Wilson 1895

The Mercantile System and Its Historical Significance by Gustav von Schmoller 1896

History of American Socialisms by George Noyes 1870 ("The only laudable object any one can have in rehearsing and studying the histories of the socialistic failures, is that of learning from them practical lessons for guidance in present and future experiments.")

Lectures against Socialism 1840

Economics and Socialism by Frederick Uttley Laycock 1895

Marxian Economics by Ernest Untermann - 1907

The Fallacy of Marx's Theory of Surplus-value by Henry Seymour - 1897

The Economic Theory of Risk and Insurance by Alan Herbert Willett - 1901

The Profits of Religon by Upton Sinclair 1918

Introduction to Economics by Alvin Saunders Johnson 1909

Introduction to Economics by John R Turner 1919

The Economics of Laissez Faire by Harris Gilbert Franklin 1920

History of the Great American Fortunes, Volume 1 by Gustavus Myers 1910

History of the Great American Fortunes, Volume 2 by Gustavus Myers 1910

History of the Great American Fortunes, Volume 3 by Gustavus Myers 1910

Great Riches by Charles William Eliot 1906

Inspired Millionaires; an Interpretation of America by Gerald Stanley Lee 1908

The Money God - Chapters of Heresy and Dissent Concerning Business Methods and Mercenary ideals in American Life by John C Van Dyke 1908

The Things that are Caesar's - a Defense of Wealth by Guy M Walker 1922

American Individualism by Herbert Hoover 1922

A Study of John D. Rockefeller: The Wealthiest Man in the World by Marcus Monroe Brown 1905

The Masters of Capital - a Chronicle of Wall Street by John Moody 1919

Men who are making America by BC Forbes 1917

John D. Rockefeller and his Career by Silas Hubbard 1904

Random Reminiscences of Men and Events by John D. Rockefeller 1909

Famous American Fortunes and the men who Have Made Them by Laura C Holloway 1889

The Life of George Peabody by Phebe A Hanaford 1870

The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie - 1901

The Life of James J. Hill - Volume 1 by Joseph Gilpin Pyle - 1917

The Life of James J. Hill - Volume 2 by Joseph Gilpin Pyle - 1917 (James J. Hill built the Great Northern Railroad without any government aid, even the right of way, through hundreds of miles of public lands, being paid for in cash)

Hidden Treasures - Why some Succeed while others Fail by Harry A Lewis 1887

The Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune by WA Croffut 1886

The Life and Ventures of the original John Jacob Astor by Elizabeth Gebhard 1915

Life of John Jacob Astor by James Parton 1865

Men and Mysteries of Wall Street by James K Medbery 1870

Some Successful Americans by Sherman Williams 1904

The Age of Big Business - a Chronicle of the Captains of Industry by Burton J Hendrick 1920

The Life story of J. Pierpont Morgan by Carl Hovey 1911

Millionaires and Kings of Enterprise by James Burnley 1901

Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie 1920

The Rise and Progress of the Standard Oil Company by Gilbert H Montague 1903

Bulls and Bears of New York by William Hale Smith 1874

Financial History of the United States by Davis R Dewey 1920

America at Work by John F Fraser 1903

The Model T Ford Car by Victor W Page 1915

Industrial History of the United States by Louis Ray Wells 1922

The Economic History of the United States by Ernest Ludlow Bogart 1914

The Industrial Evolution of the United States by Carroll D Wright 1901

Captains of Industry by James Parton 1896

The Oil-well Driller: A History of the World's Greatest Enterprise By Charles Austin Whiteshot 1905

The Story of Oil by Walter S Tower 1909

The Carnegie Millions and the Men who Made Them - being the inside history of the Carnegie Steel Company by James H Bridge 1903

The Romance of Steel - the Story of a Thousand Millionaires by Herbert N Casson 1907

Life of Jay Gould, how he Made his Millions by Murat Halstead 1892

Wizard of Wall Street and his Wealth - The Life and Deeds of Jay Gould by Trumbull White 1893

Financial Giants of America, Volume 1 by George F Redmond, 1922

Financial Giants of America, Volume 2 by George F Redmond, 1922

American Millionaires 1892

The Great Industries of the United States by Horace Greeley 1872

Jacob Henry Schiff - A Biographical Sketch 1921

Men of Business by William O Stoddard 1893

Readings in the Economic History of the United States by Ernest Lublow Bogart 1917

The Story of Bethlehem Steel by Arundel Cotter 1916

For a list of all of my disks, with links click here

Only $5.99 (I only ship to the United States)

Only $5.99 (I only ship to the United States)

Thursday, January 12, 2017

Karl Marx: An Irrelevant Man

Karl Marx: An Irrelevant Man

Mr. Smith is a writer living in Santa Maria, California. He has been a frequent contributor to The Wall Street Journal.I remember reading Karl Marx in college. The assignment was, to understate the case, a tedious experience. There is a quality about this ponderously dull man that makes the eyelids heavy, and his work is not recommended for a pleasant afternoon at the beach. In defense of Marx, however, the writing that we see is a translation, and the passage of thought from one language to another often has the effect of squeezing out the pithy phrases and the clever shades of meaning. I doubt that this happened to any significant degree with Marx, but it is still possible that he is more of a thundering bore in English than in the original German. Let’s give him the benefit of a doubt on this one.

Over the years I have also remembered Marx as a man who was simply wrong in the conclusions that he reached, but here was another judgment that couldn’t be put to rest that easily. I have always had some trouble with the word wrong in regard to Karl Marx because he wasn’t one for hitting nails squarely on heads, and his oblique phraseology didn’t lend itself to the simplicity of right and wrong. Adolf Hitler was wrong throughout Mein Kampf, but not in the sense that the word would apply to Marx. There is a certain specificity to being wrong that applies to a Hitler but not to a Marx.

It is wrong, for example, to say that Altoona is the capital of Pennsylvania, but the word cannot be so easily applied to the proposition that Altoona is, or is not, a nice place to live. Hitler would have gone with the first statement and gasped his last mortal breath insisting that it was correct. Marx would have preferred the other proposition, making fuzzy and ill-conceived statements that have no basis in fact but are hard to support or refute.

I have been rereading Marx in recent weeks, and I am turned off to the same extent that I was in my undergraduate days. I now believe, however, that I can pinpoint the reason that Karl and I just don’t get along. The word that I had sought for so many years was not dull and it was not wrong. The word for Karl Marx is irrelevant.

One will note that Marx prattled incessantly about the great class struggle. This might have had some meaning for 19th-century Europeans, but it means absolutely nothing to Americans of any century. We are a nation of individuals with very little concept of social or economic class. Our group affiliations are temporal: an afternoon cheering for the home team, a lodge meeting, or a get-together with the property owners’ association, but it ends when we step outside and become individuals again. I suppose that a contemporary American could hold his or her income up to some economic scale and find a place in a pre-selected bracket, but it really doesn’t mean much to anyone. Certainly there is no class struggle, and I don’t think that I know anyone who could define the term, or who cares enough to find out.

The Irrelevance of Labels

Marx uses the words bourgeoisie and proletarian repeatedly, and both are about as relevant to our lives as hoop skirts and butter churns. I know what the words mean, or what they meant to Karl Marx, but there are too many people who fit into both categories, or neither, for the words to have any applicability. I would be hard put to label anyone I know as one or the other. If a man repairs shoes, for example, he is probably a proletarian, but what if he owns the shop and he is the only employee? This makes him the boss and also the one who does all the work. In the great revolution, Marx would probably have him destroy himself.

Marx was obsessed with the idea of class, but to most Americans this is a vague, if meaningless, concept. We see the world as individuals, a group of divergent entities, each with a unique value and making up a collective body that is less important than its parts.

If one would ask the proverbial man-on-the-street American to pinpoint himself on a class scale, he would probably come up with an answer of sorts, but it would be offered with a shrug of the shoulders and a “Who cares?” tone of voice. Class loyalty is about one step below loyalty to a bowling team or an alumni association in human intensity. Certainly no American is going to take to the streets for the honor of the citizens in his salary bracket.

This, I believe, is the reason that Karl Marx has made so little impact on American thought processes. No one is quite sure what the man was talking about, and if they ever found out, they wouldn’t care anyway. He wasn’t evil, he wasn’t insane, and he certainly wasn’t stupid. On our side of the Atlantic, he is merely irrelevant. To put it succinctly, Karl Marx is a man with nothing to say to the American people.

Donald Smith

Mr. Smith, a frequent contributor to The Freeman, lives in Santa Maria, California.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Sunday, January 8, 2017

13 Essential Books to Shape the Libertarian Worldview

13 Essential Books to Shape the Libertarian Worldview

There are books that every libertarian should read and books every libertarian has read, but those circles don’t perfectly overlap. Here are 13 diverse book recommendations for well-rounded thinkers.Economic Sophisms – Frederic Bastiat

The great French liberal and economist Frederic Bastiat is best known for his pamphlet The Law — a scathing indictment of the threat that socialism poses to justice and the rule of law. But he produced another great work in Economic Sophisms, a collection of essays meticulously exposing and ridiculing the economic fallacies committed by his fellow deputies in the French National Assembly.

Sophisms includes his satirical “Petition From the Manufacturers of Candles, Tapers, Lanterns…and Generally of Everything Connected with Lighting” to the French legislature, asking for the government to blot out unfair foreign competition from a cheaper source of light — the sun.

Ahead of his time in many fields, he ruthlessly demolished fallacious arguments for protectionism, socialism, and redistribution with wit, humor, and incisive analysis.

Basic Economics + Applied Economics – Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell’s Basic Economics is one of the clearest introductions to the economic way of thinking and how it can be applied to a vast number of real world problems. Don’t be intimidated by its brick-like dimensions — it’s written with common sense and plain English. It’s highly readable and easy to digest in pieces, if you don’t finish it off in one sitting. If you get to the end and want more, don’t worry — you can continue “thinking beyond stage one” with Sowell’s Applied Economics.

Beyond Politics: The Roots of Government Failure – Randy Simmons

Public Choice is the most important branch of economics for understanding how and why governments work the way they do. Public Choice is essentially the science of political skepticism: using economic analysis to examine how the incentives of democracy guide the decision making of politicians, bureaucrats, voters, and special interests.

Randy Simmons’ Beyond Politics is the best and most accessible survey of Public Choice, explaining in clear and concrete terms just what things government cannot do — and what the consequences are when it tries to do them anyway.

The Problem of Political Authority – Michael Huemer

In this text, philosopher Michael Huemer exposes the shaky foundations of the most basic premises of government. Carefully tracing the implications of basic moral tenets that nearly everyone accepts, Huemer shows that the authority of the state is a chimera: there is no way to get from the ethical rules that govern how individuals should treat each other to a system that empowers a few people — “the state” — with the privileged moral position to issue coercive commands, while imposing on everyone else the moral duty to obey them. Huemer throws down the gauntlet and challenges the very notion of political authority — and with it, the special standard to which government actions are held.

The Myth of the Rational Voter – Bryan Caplan

The biggest reason why democracies choose bad policies is not selfishness, corruption, or lobbyists — it’s the voters themselves. Bryan Caplan documents the overwhelming empirical evidence that voters are not just ignorant about the most basic aspects of law, government, and economics, but they are also actively irrational in their preferences. In other words, voters are not just wrong but passionately and systematically wrong.

Worse, Caplan shows that these problems are inherent to the democratic system: voters have no incentive to be rational, well-informed, or coolheaded, and politicians have every reason to stoke prejudice and exploit voters’ ignorance. Limiting the scope of democratic power is the only sure way to limit the damage irrational voters can do.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments – Adam Smith

Everyone knows Adam Smith’s magisterial work The Wealth of Nations, but his first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, is essential for laying the ethical, psychological, and sociological groundwork for his later work in economics and philosophy. Today, Adam Smith is frequently demonized as the patron saint of greed and selfishness, but Moral Sentiments shows that Smith had a nuanced and deep understanding of human nature, our drives for virtue and vice, and the spirit and sympathies that help human beings thrive.

This book, published in 1759, was vastly ahead of its time in many fields, foreshadowing later developments in social science, moral philosophy, and social psychology. But it is also packed with deep and practical insights for any student of human nature. If you find Smith a little too daunting on the first attempt, Russ Roberts’ How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life is a short and friendly introduction to some of the insights in Moral Sentiments.

The God of the Machine – Isabel Paterson

First published in 1943, The God of the Machine was one of four books that emerged in the depths of World War II — along with Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, and Rose Wilder Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom — that launched the modern libertarian movement and helped turn the intellectual tide against collectivism.

At a time when socialism and fascism were conquering whole continents, Paterson set out a defense of individualism, the free market, and limited government that remains powerful and timely to this day. By tracing the role of individual freedom in the rise and fall of civilizations, the book re-centered the discussion of human history on its true subject: the individual.

No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority – Lysander Spooner

Legal theorist Lysander Spooner wrote this devastating critique of the U.S. Constitution in 1867. It remains one of the most thoughtful and hard-hitting criticisms of the American government and federal power. Spooner illustrates why the Constitution can carry no binding authority as a “contract” among “we the people.” At most, he argued, it could only bind and apply to the people who were actually alive at the time of its adoption, and then only to those who explicitly consented to its adoption. Therefore, breaking away from the union of states is “no treason.”

No Treason is also one of the most quotable individualist anarchist works. Any anarchist worth his or her salt knows by heart Spooner’s concise indictment of the Constitution: “But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain – that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist.”

Radicals for Capitalism – Brian Doherty

Radicals for Capitalism is a weighty tome, summarizing centuries of classical liberal and libertarian history in one book. Reason magazine senior editor Brian Doherty goes to great lengths to capture the varying influences and factions within the broader libertarian movement. This book is an essential part of any collection on American political history, and friends of liberty will find a lot to learn and enjoy in its eyewitness histories and firsthand accounts of the motley crew that created and compose the modern American libertarian movement.

Democracy in America – Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville came to the United States to study prisons for the French government, but he ended up making his most important contributions by studying America’s free society in action. De Toqueville toured the country for nine months, observing how U.S. political, economic, religious, and social institutions worked together to foster human cooperation, and how that process of cooperation led to a thriving social order.

As Daniel J. D’Amico explains, “America’s early and rapid rate of economic development and its functioning social order resulted from a life spring of vibrant civil society. Families, clubs, churches, and various community groups provided early Americans with diverse opportunities to practice the art of association.”

The text, first published in 1835, endures as an influential and insightful account of American society and culture — it has been called the best book ever written about America — but more importantly, it describes the principles underlying social order itself. “In democratic countries the science of association is the mother science,” De Tocqueville wrote, “the progress of all the others depends on the progress of that one.”

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress – Robert Heinlein

This novel explores a futuristic society in which a lunar colony revolts against rule from Earth. It is widely regarded as one of the best science fiction novels of all time, but its compelling portrait of a dystopian future and discussion of libertarian ideas make it an essential part of a libertarian bookshelf. Characters in the book range in their politics from self-proclaimed anarchist to would-be authoritarian, and the novel touches on libertarian themes such as spontaneous order, natural law, and individualism. Harsh Mistress would go on to win various awards, including the Hugo Award for best science fiction novel.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich – Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

“The days rolled by in the camp — they were over before you could say ‘knife.’ But the years, they never rolled by; they never moved by a second.”

In this short novel, Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn lays out — in brutal detail — an ordinary day in the life of one prisoner held in Stalin’s Siberian gulags: the bitter cold, the pervasive hunger, the savage punishments, the powerlessness, despair, and fear. Solzhenitsyn himself spent ten years in the gulag for insulting Stalin, and his own personal experience sharpens the story with heartbreaking detail. Tens of millions were churned through the gulags and slave labor camps in the Soviet Union; more than one million people would die there. Ivan Denisovich helps to humanize an ocean of terror and human suffering that all too easily blurs into a pile of statistics.

This piece ran at the LearnLiberty Blog

Daniel Bier

Daniel Bier is the editor of the LearnLiberty blog, and contributing editor of FEE. He writes on issues relating to science, civil liberties, and economic freedom.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)