The Yellow Press - The Fake News of the Past by Sydney Brooks 1911

The late Mr. Joseph Pulitzer was unquestionably one of the most remarkable personalities of latter-day America. Indomitable by nature, of quick, unshackled perceptions, passionate to learn and to experiment, and with a strong vein of idealism running through his lust for power and success and domination, he was fortunate in the fate that landed him, forty-seven years ago, in Boston when America was on the very point of plunging into the most amazing era of material development and exploitation that the world has yet witnessed. The penniless son of a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, young Pulitzer shifted from one occupation to another before he finally found his life-work in journalism. He was a soldier, a steamboat stoker on the Mississippi, a teamster, and, some say, a hackman and a waiter by turns before he became a reporter on a St. Louis newspaper. Once in journalism his daring and imagination and his avidity to master every detail of his profession quickly carried him to the front. He bought a St. Louis evening paper and converted it into the Post-Despatch, working it up into one of the most influential journals and most valuable newspaper properties in the Middle West. In 1883 he purchased from Jay Gould the New York World, and almost to the day of his death, in spite of long absences and the appalling affliction of blindness, he remained its director and inspiration. Under his dashing guidance the World became the most fearless, the most independent, the most powerful, and also the most sensational journal in the United States. On the occasion of his sixtieth birthday Mr. Pulitzer sent a message to his staff in which he embodied his conception of a great newspaper: "An institution which should always fight for progress and reform; never tolerate injustice or corruption; always fight demagogues of all parties; never belong to any party; always oppose privileged classes and public plunder; never lack sympathy with the poor; always remain devoted to the public welfare; never be satisfied with merely printing news; always be drastically independent; never be afraid to attack wrong whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty." And in a codicil to his will, published on November 15th, he reiterated his journalistic ideals in the form of a last request and admonition to his sons: "I particularly enjoin on my sons and descendants the duty of preserving, perfecting, and perpetuating the World newspaper, to the maintenance and publishing of which I have sacrificed my health and strength, in the same spirit in which I have striven to create and conduct it as a public institution from motives higher than mere gain, it having been my desire that it should be at all times conducted in a spirit of independence and with a view to inculcating high standards and public spirit among the people and their official representatives; and it is my earnest wish that the said newspaper shall hereafter be conducted on the same principles." These are high professions of faith, and the World in many ways has not fallen below them. Time and again Mr. Pulitzer risked popularity and gain and offended many powerful interests rather than compromise where he thought compromise to be wrong. Often reckless, prejudiced, and unfair in his onslaughts, he nevertheless rendered many public services, withstood the clamour of the hour at more than one fateful crisis, and preserved inviolate and incorruptible his ideal of independence. He was a man of real public spirit and of genuine political instinct, and the large sums he devoted to establishing a school of journalism in Columbia College bore witness to a pride in his profession to which no member of it can be indifferent. In his own distinctive phosphorescent way he meant to be, and was, a force for righteousness.

It is probable, however, that when the memory of his individuality has faded, Mr. Pulitzer will be chiefly remembered as the Father of the Yellow Press, or, at any rate, as the man who, if he did not originate yellow journalism, so greatly extended it as to make it appear his own invention, and who, if he left some of its least creditable excesses to others, was for long its best known and most pyrotechnical practitioner. In that capacity his practice did not always square with his principles. There is no more vigorous or higher-minded journal in the United States than Collier's Weekly. In paying tribute to Mr. Pulitzer's memory and in emphasising the vastness of the opportunity open to his sons and successors, that admirable organ recently remarked: "Upon them is the burden of showing originality and strength, like their father, but of applying those qualities to a changing era. The forward spirit that he showed in attacking social feudalism, they will find themselves called upon to apply to the pressing task of helping to take graft and falsehood out of journalism itself. He never cared to do his share toward removing the loan shark and the patent-medicine poisoner by forbidding them the use of his own columns. The news also needs to be treated with more responsibility. We will give an instance from a recent day. A young stenographer, passing from a street car to her home a block away after nightfall, felt a

man's fingers clinch about her neck, and when she reached her hands towards the fingers she found that they were very large. Twenty minutes later the girl's mother found her on the sidewalk, weeping hysterically, and able to remember only that she had been strangled. Next day in the Evening World it was stated on the authority of an examining physician that the girl's skull was fractured, her jaw broken, her breasts, face and arms terribly bitten, 'as a mad dog might have torn the victim of an infuriated attack,' and her body covered with bruises from blows struck by a club of which the girl cried out deliriously; lusty bloodhounds led a horde of officers in uniform and a score of detectives across the countryside. Actually there were no bloodhounds, no pursuing policemen in uniform, no bites, no fractured skull, no broken jaw, no body bruises, and no club. As Joseph Pulitzer served his generation in his own direction, so his sons, we are sure, will serve a later generation in the light of present morals." This willingnesss to sport with the facts and to insist on extracting "a thrill" from every incident is one of the distinctive characteristics of the Yellow Press. The World has been by no means immune from it. I remember reading in its columns a long interview with Mr. Pierpont Morgan of a most sensational character, and admirably contrived to embitter the working man against the capitalists. Mr. Morgan's inaccessibility to journalists is notorious, and the statements he was alleged to have made were of a kind to stamp the whole interview as a concoction from beginning to end. In a subsequent issue, when the damage had been done, the World acknowledged that it had been "imposed upon." At the same time, and side by side with its retraction, it published a series of comments on the alleged interview from a number of newspapers — a proceeding that might well have been taken as the text for a lecture in Mr. Pulitzer's School of Journalism.

To put the American Yellow Press in its proper light, one must remember that journalism, while a giant, is a very young one. In its present form it is the product of a quick succession of astounding inventions. The railway, the cable, the telegraph, the telephone, the rotary press, the linotype, the manufacture of paper from wood-pulp, and colour-printing — these are the discoveries of yesterday that have made the journal of to-day possible. We are still too near to the phenomenon to be able to assess its significance, or to determine its relations to the general scheme of things. Journalism still awaits its philosopher: awaits, I mean, someone who will work out the action and reaction of this new and tremendous power of organised, ubiquitous publicity upon human life. It has already, to all appearances, taken its place among the permanent social forces; we see it visibly affecting pretty nearly all we do and say and think, competing with the churches, superseding parliaments, elbowing out literature, rivalling the schools and universities, furnishing the world with a new set of nerves; yet nobody that I am aware of has yet attempted to trace out its consequences, to define its nature, functions, and principles, or to establish its place and prerogatives by the side of those other forces, religion, law, art, commerce, and so on, that, unlike journalism, infused the ancient as well as the modern world. Journalism is young, and the problems propounded by the necessity of adjusting it to society and the State have so far been hardly formulated. Its youth must be its excuse for whatever flaws and excesses it has developed. The Yellow Press, as I view the matter, is a disorder of infancy and not of decrepitude; it is a sort of journalistic scarlet fever, and will be cured in time. And there are many reasons why it should have fastened upon America with particular virulence. Journalism there has run through three main phases. There was first, the phase in which a paper was able to support itself by its circulation alone, in which advertisements were a minor consideration, and in which the editor, by his personality, his opinions, and his power of stating them, was the principal factor. But the day of the supremacy of the leading article perished soon after the Civil War, and there set in the era — it is just beginning with us — when the important thing was not opinion but news, and when the advertisers became the chief source of newspaper profits. Speaking broadly, the centre of the power of the Press in the United States has shifted from the editorial to the news columns. Its influence is not on that account less operative, but it is, I should judge, less tangible and personal and more diffused, dependent, that is to say, less on editorial comment than on the skill shown in collecting the news of the day and in presenting it in a form that will express particular views and policies. The ordinary American journal of to-day serves up the events of the preceding twenty-four hours from its own point of view, coloured by its own prepossessions and affiliations, and the most effective propagandism for or against a given measure or man is thus carried on continuously, by a multitude of little strokes, in the news columns, and particularly in the headlines attached to them. Now the Americans have always taken a liberal, if not a licentious, view of the kind of news that ought to be printed. In a somewhat raw, remote, free and easy community, impressed with the idea of social equality, absorbed in the work of laying the material foundations of a vast civilisation, eminently sociable and inquisitive but with comparatively few social traditions and almost no settled code of manners, it was natural enough that the line between private and public affairs should be loosely drawn. Moreover, the Americans have never enjoyed anything like the severity of our own libel laws. The greater the truth the greater the libel is not a maxim of American law. On the contrary, a statement, if published without malice, is held to be justifiable so long as it can be shown to be true. Attempts have been made in some States to elevate a published retraction into a sufficient defence in a suit for libel, and to invest a reporter's "copy " with the halo of "privileged communication." Then, again, there is nothing in America that at all corresponds to our law of contempt of court. An American paper is entitled to anticipate the probable findings of a judge and jury, to take sides in any case that happens to interest it, to comment on and to garble the evidence from day to day, to work up sympathy for or against the prosecutor or defendant, and to proclaim its conviction of the guilt or innocence of the prisoner from the first moment of his arrest and without waiting for the tiresome formality of the verdict. Hardly an issue, indeed, appears of even the most reputable organs in the United States, such as the New York Sun, The Times, and the Evening Post, that would not land its publisher and editor in prison if the English law of contempt of court obtained in America.

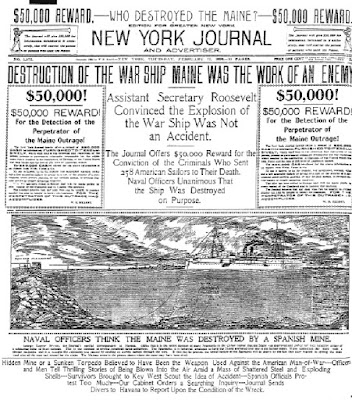

Conditions such as these favoured from the first the species of journalism which the world has agreed to designate as yellow. When James Gordon Bennett, for instance, started the New York Herald, he specifically, as he himself said in his salutatory, "renounced all so-called principles." He set out to find the news and to print it first; the more private and personal it was the better. He was more than once horse-whipped in the streets of New York. But that did little good. Bennett's reply was to bring out a flaming "extra" with a full account of the incident written in his own pungent English. The more he was horse-whipped the more papers he sold. From the success of the New York Herald may be dated that false conception of what news is, of the methods that may be employed in getting it, and of its importance to a newspaper that has since permeated nearly all American journalism. Mr. Pultizer and Mr. Hearst have in reality done little more than to devote inexhaustible ingenuity, wealth, and enterprise to working the soil which Mr. Bennett long ago was the first to break. But their form of cultivation has been so intensive as to constitute by itself the third of the three phases through which American journalism has thus far passed! The Yellow Press existed long before it was christened. It was not, indeed, until 1895, when Mr. Hearst came to New York intent on beating Mr. Pulitzer on his own ground and by his own weapons, that the type of journalism which emerged from their resounding conflict was labelled "yellow." As a mere uninitiated Englishman, resident at that time in New York, it seemed to me a contest of madmen for the primacy of a sewer. Sprawling headlines, the hunting down of criminals by imaginative reporters, the frenzied demand for their reprieve when caught and condemned, interviews that were "fakes" from the first word to the last, the melodramatisation of the follies of the Four Hundred, columns of gossip and scandal that could only have emanated from stewards in the fashionable clubs or maids and butlers in private houses, sympathetic reports from feminine pens of murder, divorce, and breach of promise cases with a sob in every line, every incident of the day tortured to yield the pure juice of emotionalism beloved of the servants' hall — such was the week-day fare provided by the Yellow Press in those ebullient days. On Sundays it was much worse. It is on Sunday that the American papers, yellow and otherwise, put forth their finest efforts and produce their most flamboyant effects. The Sunday edition of a New York daily is a miscellany of from sixty to eighty pages that in mere wood-pulp represents a respectable plantation and that would carpet a fair-sized room. Of all its innumerable features the most distinctively yellow is the comic supplement printed in colours. Nothing better calculated to kill the American reputation for humour has ever been conceived. It is a medley of knock-about facetiousness, through which week after week march a number of types and characters — Happy Hooligan, Frowsy Freddy, Weary Willie, Tired Tim, and so on — whose adventures and sayings make up a world that resembles nothing so much as a libellous vision of the cheapest music hall seen in a nightmare by a madman. And among the other attractions of these Sunday editions you will usually find a page or two given up to the doings and photographs of those preposterous actors and actresses who are so woefully smaller than the art they practise; and another page, fully illustrated, to society news and scandal; and a third page, and, with luck, a fourth, to the latest crime. The Yellow Press has consistently specialized in crime. I recall a famous issue of one paper that described and illustrated a hundred different ways of killing a man; and, indeed, a would-be criminal could hardly hope for a better school in which to master the theory of his profession. Pictures of men in masks in the act of blowing open a safe, of an embezzling cashier stepping on to the train for Mexico, of a drunken man assaulting his wife with a bootjack, of a youth drowning a girl he has betrayed, reproductions of the faces of murderers, of the rooms in which and the weapons with which their crimes were committed, precise and detailed descriptions of the latest swindling trick or embezzlement device or confidence game — even, in one case, I remember, a column and a half of exact information on the construction of an infernal machine and the best way of packing it so as to avoid detection in the post office — these are the aids with which the Yellow Press strews the path of the budding burglar, thief, and criminal.

But perhaps its greatest offence is its policy of perverting the truth in the interest of a mere tawdry sensationalism, of encouraging the American people to look for a thrill in every paragraph of news, of feeding them on a diet of scrappy balderdash. This habit of digging away for what is emotionally picturesque and "popular" has infected almost the whole of the American daily Press. Only a few months ago a professor of moral philosophy at Harvard was bewailing how egregiously he had been victimised by this policy. He was delivering an address at a girls' college in Boston on the higher education of women, and in the course of it he mentioned the case of a girl-student who had become so absorbed in her work as to lose all interest in social diversions. Her parents and friends pressed her to slacken off for a year or so and devote more time to balls and luncheons and so on. She came to him, the professor, for advice, and he counselled her to do as she was urged. "Flirt," he said, "flirt hard and show that a college girl is equal to whatever is required of her." The professor, as I said, in the course of his address, which took about a hour to deliver, recalled this incident. He did not dwell on it; he made no other reference to it whatever; he said nothing at all about the place that flirtation should hold in a properly organised curriculum. That same evening a Boston paper came out with a report of his "Address on Flirtation." The next day he was asked for but declined an interview on the subject. The interview, however, appeared, a column of imaginative literature, generously adorned with headlines and quotation marks, setting forth in the gayest of colours his "advocacy of flirtation." The professor, not being an ardent newspaper reader, did not realise what had happened until there suddenly began to rain upon him a succession of solemn or derisive editorials, letters from distressed parents, abusive post cards, and leaflets from societies for the prevention of vice with the significant passages marked. The bubble grew and grew; "symposia" were held by scores of papers on whether girls should flirt; the topic raged over the continent; and it soon became a settled conviction in the minds of some ninety million people, who at once proceeded to denounce his hoary depravity, that the professor of moral philosophy at Harvard was advocating a general looseness in the relations of the sexes. And that is the sort of buffoonery to which any man who opens his mouth in public in the United States is inevitably exposed.

But not all of the enormities of the Yellow Press were of their own commission. They fostered an appetite for sensationalism, and all sorts of news-bureaus and Press agencies came into existence to gratify it. More than once the yellow journals found themselves hoist with their own petard and tricked into publishing incidents that had never the slightest basis in fact. It is on record, for example, that the editor of one of these news agencies conceived one day a wonderfully plausible story of an attempted suicide in a fashionable doctor's office, the would-be suicide being rescued only by the timely intervention of the doctor. The thing never happened, but it might have happened, and he sat down and wrote a realistic account of it. This account he handed to a girl on his reporters' staff, telling her to take it to some prominent doctor and convince him of the numberless advantages, the prodigious advertisement, that would accrue to him if only he would endorse the tale. The first doctor she approached said he could stand a good deal in the way of exaggeration, but that he was not yet educated up to the point of swearing to the truth of a story that was an absolute lie. The second, a physician known all over New York, bundled her out of the house in double-quick time. At the third attempt she was successful. She found a doctor, and a well-known one, too, who was delighted with the idea, and gladly closed with her proposal. They went over his consulting room together; the cord with which the patient had tried to strangle herself during the momentary absence of the doctor, the lounge to which she was removed, the restoratives applied, were all agreed upon. The story was then sent out to the newspaper offices; the doctor, being appealed to by the reporters, confirmed it in every detail; and it appeared in the next morning's papers, three-quarters of a column of soul-moving narrative, with the doctor's photograph and a sketch of his consulting room, and this final paragraph: "Owing to the urgent pleadings of the lady, Dr. refuses to give the name and address of his patient, but says she belongs to one of the wealthiest and most exclusive social circles in the city." On the whole it would not be easy to conceive a deeper abyss of infamy.

It sometimes happened that the ingenuity of the sensation-mongers was wasted. When Mr. Henry Miller, for instance, was about to make his first appearance in New York as a star in a new play he received the following letter from the editor of one of these news bureaus: "Dear Sir,—You are probably aware that nowadays it is sensation and not talent that wins. As you are to make your first stellar appearance in New York, it is almost necessary that you do something to attract attention, and I have a scheme to propose. On Sunday night your house will be entered by burglars. They will turn the place upside down, and upon discovery pistol-shots will be fired. They will escape, leaving blood-stains upon the floor. You will get the credit of fighting single-handed two desperate robbers. The New York Herald and the other morning dailies will get the story and the whole town will be talking about you. I will furnish the burglars and take all chances, and will only charge $100 dollars for the scheme." Mr. Miller declined the offer, but it is amazing to discover whither the passion for advertisement in that land of advertisement will lead people. I remember seeing in a New York paper a long article describing a house of Pompeian design, built of glass bricks and glass columns of all colours, that was to be erected at Newport for a Western millionaire by a well-known firm of city architects, whose name and address were given and who supplied the paper with interior and exterior plans of the projected building. It turned out that no such freak was ever contemplated, and that the architects, for such advertisement as it would give them, and the reporter, hungering for a sensation, had concocted the tale between them. To the same genesis, I should say, may be ascribed a paragraph about a chiropodist who announced that he had replaced a missing toe with one of solid gold. The weapon which the Yellow Press had forged was, in short, turned against them. There were cases in which conspiracies were formed between reporters and unscrupulous outsiders to procure the insertion of paragraphs and articles on which a libel action could be based against the papers publishing them. There were cases, too, in which the reporters who were detailed on some special mission — say, to interview the jurymen after a famous murder trial — would get together, ignore the refusal of the jurymen to be interviewed, and write out, each in his own style, what they ought to have said. There is really something more than jest in the old remark that Shakespeare would never have suited a New York newspaper; he had not sufficient imagination.

But the Yellow Press is not al1 evil and inanity. It has its virtues and its usefulness. The calculation which was the base of Mr. Hearst's invasion of New York was this. He added up the figures of the circulation of all the New York papers and compared them with the census returns of population. He found that there was a large number of people in New York who apparently never read, or at any rate never bought, a paper at all. These were the people he set out to cater for, and it is undoubtedly one of the merits of the Yellow Press that it has forced people to read who never read before. That, it may be said, is not rendering much of a service to the community if the type of reading was such as I have described. Well I think that is arguable. In the first place, not all the columns of the Yellow Press, even in its yellowest days, were filled with the frivolities and slush I have touched on; and in the second place, Mr. W. Irwin, who has contributed this year a brilliant series of articles to Collier's Weekly on American journalism, notes the very interesting fact that Mr. Hearst's papers, which one may take as fairly representative of the Yellow Press, appear to change their clientele once every seven or eight years. From this Mr. Irwin comfortably infers that in general the more a man reads the better he reads. Once implant a taste for reading and the odds are that it will unconsciously improve itself, and will in time come to discard the tenth-rate in favour of the ninth-rate. Those who begin with Mr. Hearst's organs gradually find them out, grow disgusted, and desire something better. Sounder standards are thus in process of evolution all the time, and even the Yellow Press is affected by them and finds it to its interest to conform to them. Then, too, the Yellow Press attempts so much and covers such a wide field of life that some of its enterprises, by the mere law of averages, are bound to be beneficent. The New York American, for instance, in its news as well as its editorial columns has always paid special attention to matters of public health and domestic hygiene and the rearing of children and the care of the sick. In its own peculiar way, I should say it has sincerely tried to civilise its readers and make them think. Its columns have been the means of remedying hundreds of little injustices to the poor. A reader of the American or of the Evening Journal who is oppressed by his landlord or by the police, finds in his favourite paper a ready champion of his wrongs. The American is constantly risking the patronage of its advertisers by fighting drink and cigarettes. It is prolific of semi-philanthropic activities. At the time of the Galveston flood and the San Francisco earthquake Mr. Hearst sent three full trains of provisions, clothing, medicines, doctors, and nurses across the Continent. The American conducts an admirable fresh-air fund; it takes a hundred children from the tenements every day throughout the summer for a day's outing at the seaside; it offers each year a two-weeks' vacation to the entire family having the largest number of children in the New York public schools; it distributes free ice in summer and free soup in winter and cartloads of toys at Christmas time; it is a newspaper, an adult kindergarten, and a charitable institution rolled into one. In the last Sunday edition that I happened to see, along with the comic supplement and plenty of inane gossip, I found an admirable article by d'Annunzio on the Italian expedition to Tripoli, and a very well-written and well-illustrated page given up to a popular digest of one of Reclus' works on anthropology. The Yellow Press gets most of what is bad in life into its columns but it does not exclude what is better. There is usually something to be found in itthat is really instructive, and presented in a simple and stimulating fashion. It displays, of course, no sense of proportion. whatever in arranging its news and in deciding between what is of real and permanent interest and what is merely and vulgarly ephemeral; the Christmas edition of a typical Yellow journal might easily print on one page Milton's Ode on the Nativity and on the next several columns of sketches and letter-press commenting on and illustrating the various styles of walking to be seen on Fifth Avenue among the members of the Four Hundred; but it is not irredeemably degrading.

But, besides all this, the Yellow Press in Mr. Pulitzer's and Mr. Hearst's hands has rendered some real public services. While most of the American daily papers in the big cities are believed to be under the influence of the "money power" and controlled by "the interests," the Yellow journals have never failed to flay the rich perverter of public funds and properties, the rich gambler in fraudulent consolidations, and the far-reaching oppressiveness of that alliance between organised wealth and debased politics which dominates America. They daily explain to the masses how they are being robbed by the Trusts, juggled with by the politicians, and betrayed by their elected officers. They unearth the iniquities of a great corporation with the same microscopic diligence that they squander on following up the clues in a murder mystery or on collecting or inventing the details of a society scandal. Their motives may be dubious and their methods wholly brazen, but it is undeniable that the public has benefited by many of their achievements. The, American criminal, whether he is of the kind that steals a public franchise or corrupts a legislature, or of the equally common but more frequently caught and convicted kind that rifles a safe or kidnaps a child, fears the Yellow Press far more than he fears the police or the public. Both Mr. Hearst and the late Mr. Pulitzer have not only saved millions of dollars to the public, but have fought a stimulating fight far democracy against plutocracy and privilege. The Yellow Press, in short, has proved a fearless and efficient instrument for the exposure of public wrongdoing. The political power which Mr. Hearst has built up on the basis of his Continental chain of journals represents something more than cheek and a cheque-book, pantomime and pandemonium. What gives him his ultimate influence is that he has used the resources of an unlimited publicity to make himself and his propaganda the rallying centre for disaffection and unrest. With more point and passion and pertinacity than any other agency, his papers have stood for the people against the plutocracy, and for trade unions against capital, have assailed the "money power" and its control over the instruments of Government, have let daylight into the realities of American conditions, and have given pointed and constant expression to that weariness with the regular parties which is now pretty nearly a national sentiment. Daily expounded by Mr. Arthur Brisbane in the columns of the New York Evening Journal in a sharp, staccato, almost monosyllabic style of unsurpassable crispness, lucidity, and plausibility, set off with a coruscation of all known typographical devices, the Hearst creed and the Hearst programme have powerfully affected the imagination of the American, or at any rate the New York masses. There is no stranger or more instructive experience than to get on a subway train in New York during the hours of the evening homeward rush and watch the labourer in his overalls, the tired shop-girl, and the pallid clerk reading and re-reading Mr. Brisbane's "leader" for the day. He has, I suppose, a wider audience than any writer or preacher has had before. Always fresh and pyrotechnical, master of the telling phrase and the capitivating argument, and veiling the dexterous half-truth behind a drapery of buoyant and "popular" philosophy and sentiment, Mr. Brisbane has every qualification that an insinuating preacher of discontent should have. He, at any rate, has made the masses think — no man more so; the leading article in his hands has lost all its stodginess and restrictions, and become a vital and all-embracing instrument. That is something which would have to be borne in mind if one were to attempt the interesting but very serious task of estimating the influence of the Yellow Press on the American mind and character, and of determining how far it is responsible for, and how far the outcome of, the volatility and empiricism, the hysterical restlessness and superficiality, and the incapacity for deep and sustained thinking that have been noted in the American people. It seems hardly possible that even America should not pay something for its Yellow Press. I believe, however, that it is called upon to pay less and less as the years go on, and that the worst and most reckless days of yellow journalism are over.